The following story is a CC0-licensed contribution to Wanderverse. It's the sequel to "Soul Juice," but you can enjoy this piece regardless of familiarity with that one.

My work developing Wanderverse is enabled by Sonya Supposedly members, for which I am incandescently grateful 💖 Seriously, I feel the glow and I hope that you do too.

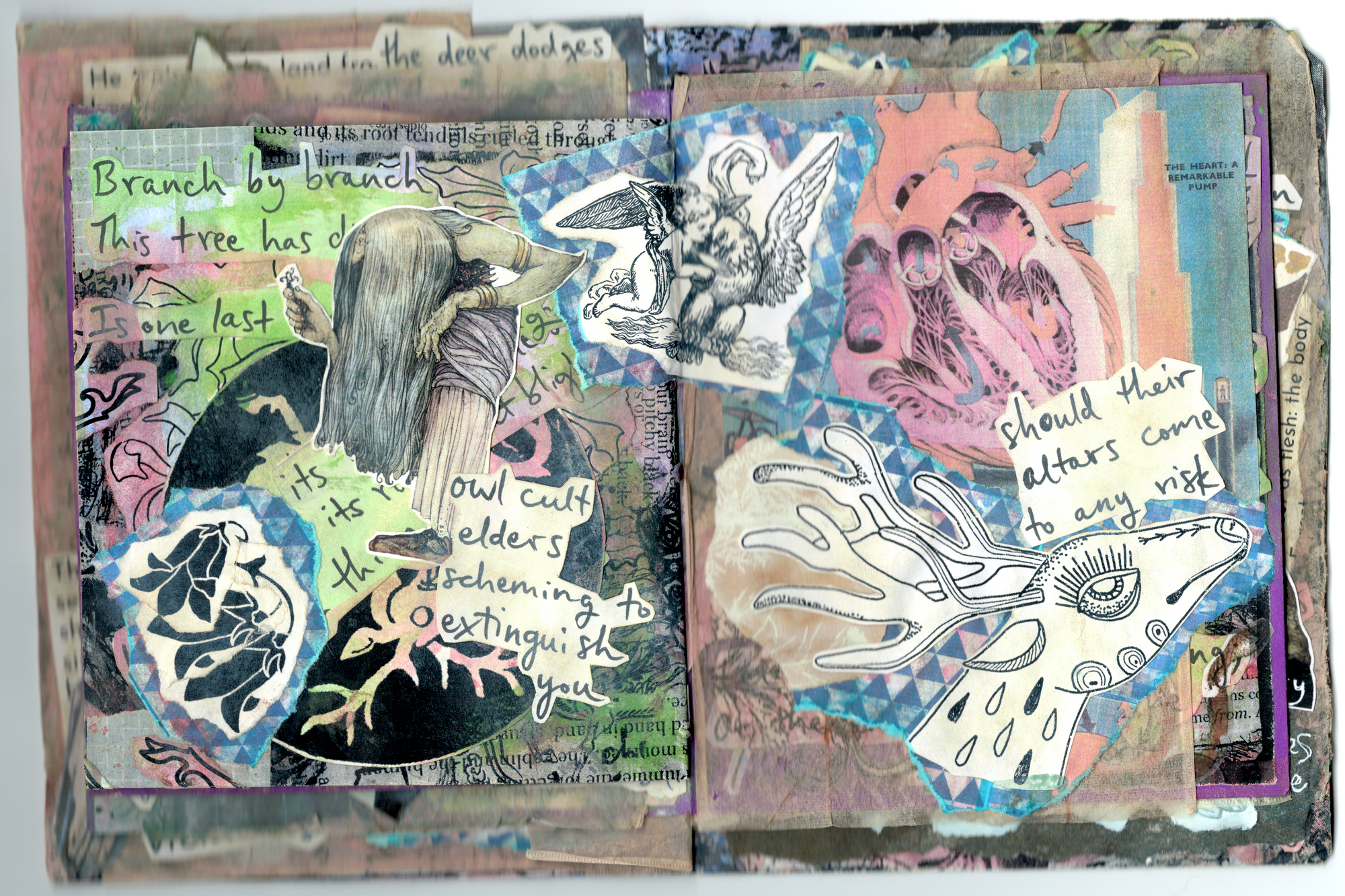

A part of you is cut away in the forest. It lies pathetic on the dead leaves, bleeding and convulsing. You continue forward.

The forest doesn't want you. It tries to push you away. The trees withhold their secrets. You hear the scream of a fox, then a stag. These woods are dangerous and you are injured already. A tempting target.

Soon, of course, they seize you. "It's time!" one predator declares with excitement. You know it's time. Time has never not been the ultimate culprit.

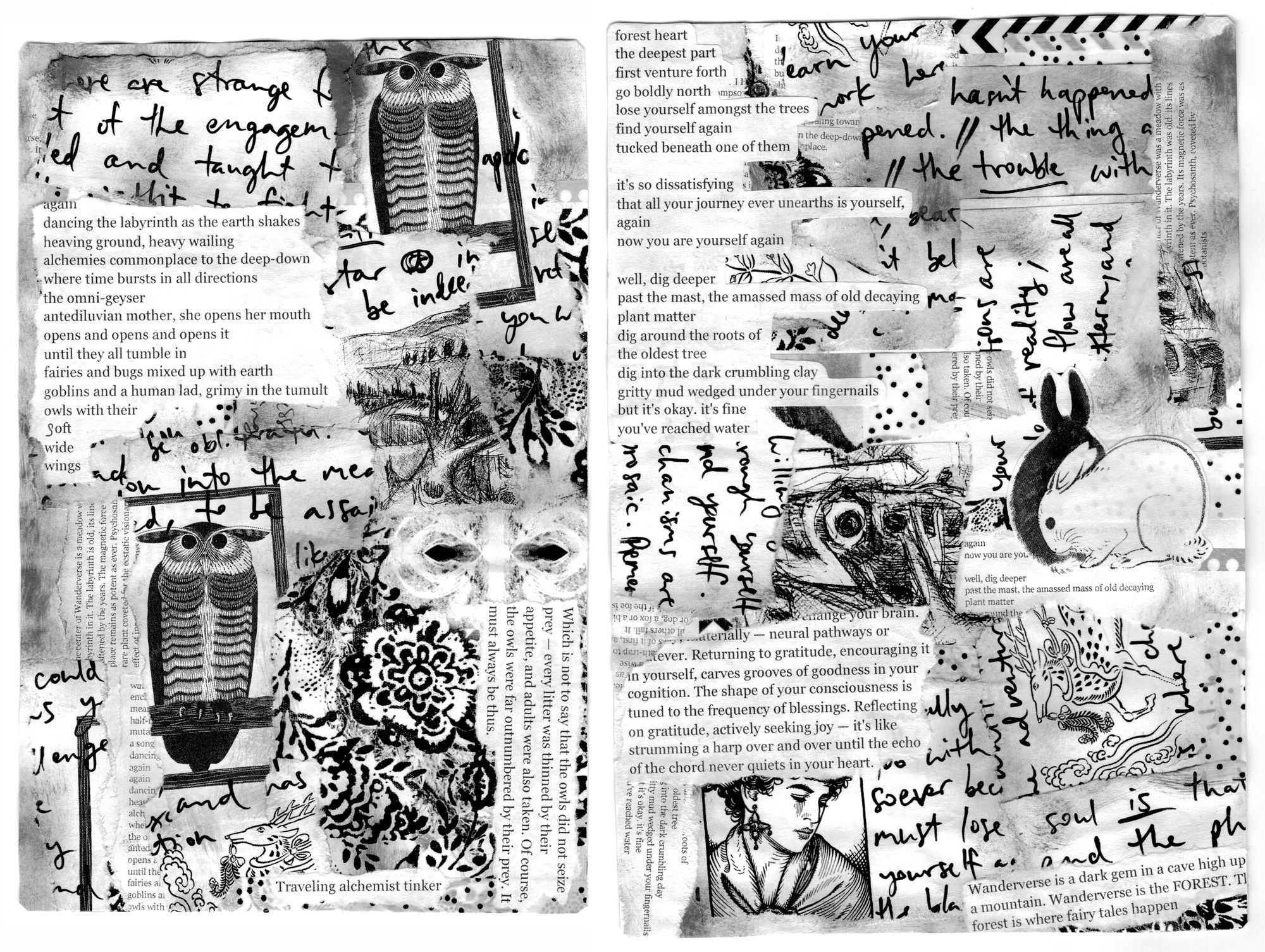

Now you are in a clearing, presided over by a council of owls. It is twilight and indigo cloaks your eyes. The tallest owl gestures emphatically with his long wing and releases a burst of pale feathers. You are still weak. Still bereft of what you abandoned in the woods.

The thing about the future is that it hasn't happened yet. The thing about the past is that it won't stop having happened. The trouble with the future is that it's going to happen eventually. It rolls forward, an inexorable becoming.

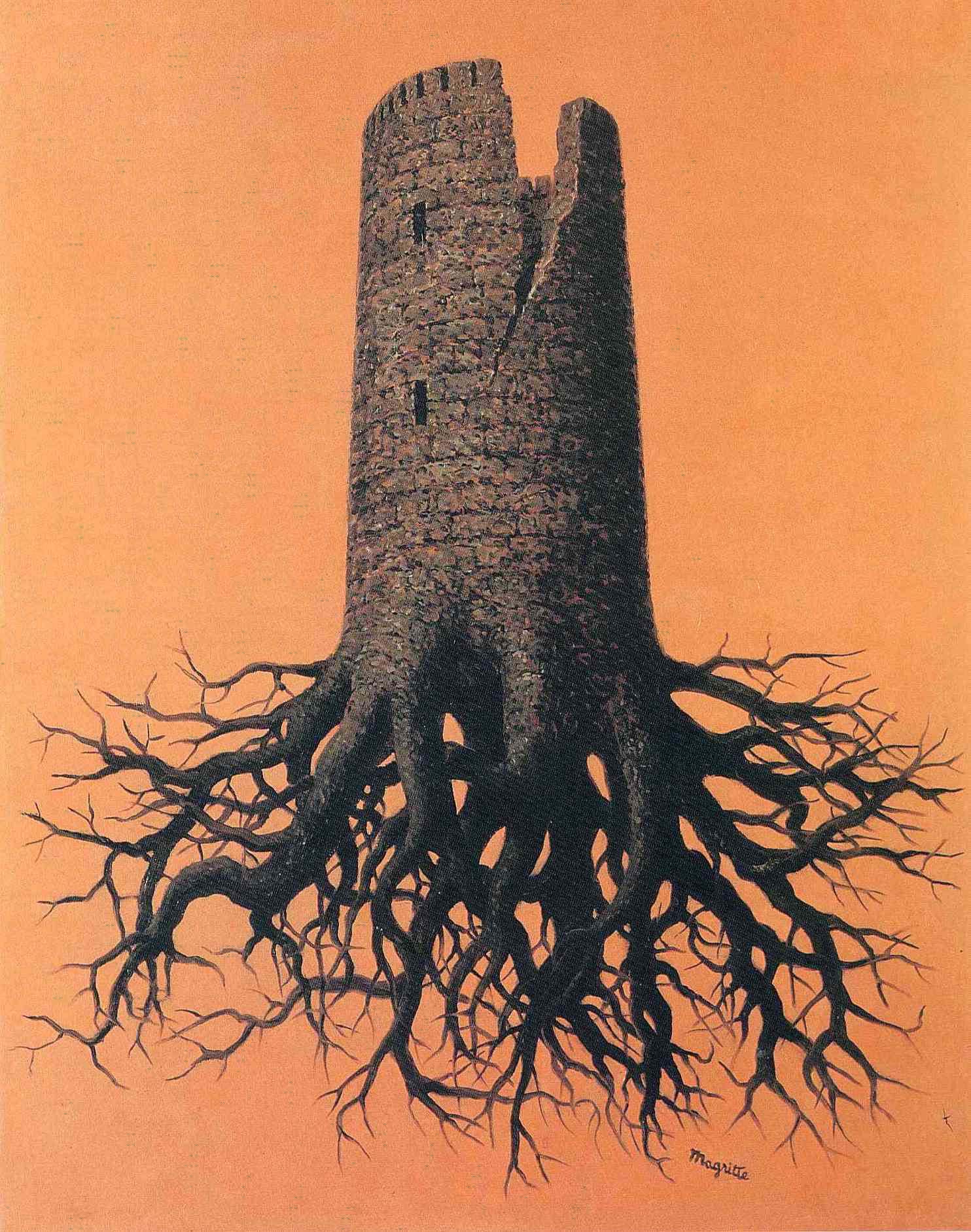

The center of Wanderverse is a meadow with a labyrinth in it. The labyrinth is old, its lines softened by the years. The magnetic force of the place remains as potent as ever. Psychosanth, a rare plant coveted for the ecstatic visionary effect of ingesting its sap, draws on the same energy as the owl cult and other devotees of the labyrinth and travelers drawn in by its pull. Psychosanth depends on Elkatron, lady behemoth shuddering and sobbing in the earth, slavering and convulsing. In the darkest deep-down.

In the darkest deep-down, the deep darkest down, Elkatron wept. Her disturbance groaned through the ground. It shuddered up and up, it bubbled and blistered. Her tears flowed into the channels of the earth, her spit and her blood and her grinding lamentation mixed with mineral dust, diluted amongst the cool flowing water, spiraling toward the root-tips of old trees. In the deep-down these alchemies are commonplace.

On the surface, the labyrinth cracked. The gazebo creaked and slumped sideways. The owls beat their soft wide wings. The bugs loop-de-looped into the sky, followed by seed fairy Plumule, the forgetting daughter, the child who is mourned. The goblin and the human gripped hand in hand, struggling to keep their balance.

The psychosanth plant drank up Elkatron's fluids and its root tendrils curled through the shifting dirt.

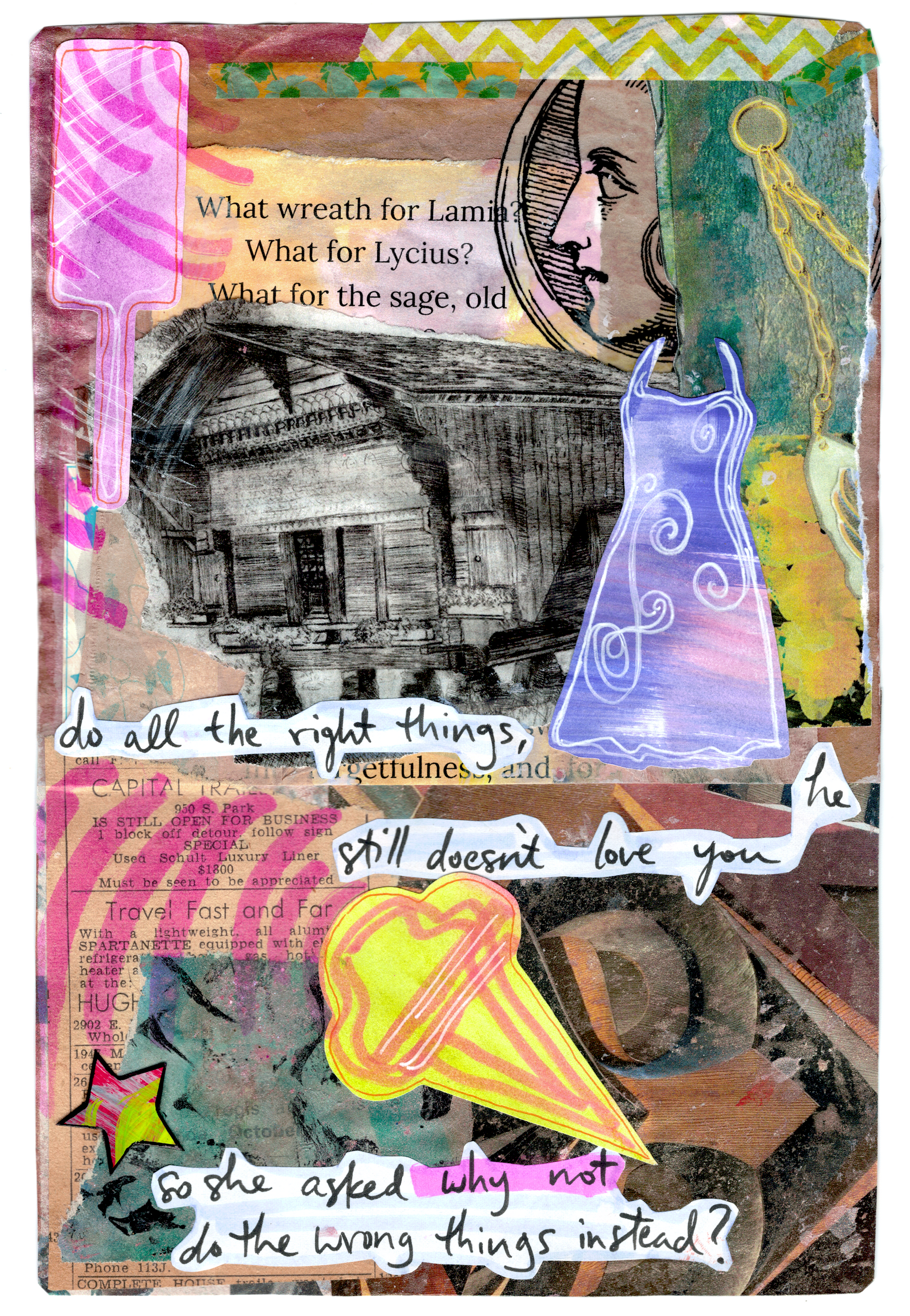

Every wood has a witch in it. This one hides.

At the appropriate hour she spun an enchantment about her cottage like the layers of gossamer cobweb that conceal a spider's prey. Her charm was cleverly fashioned to repel any foreign gaze.

The witch's caution is because her home is nestled among the trees not far from the clearing where the sacred labyrinth was carved so long ago. That meadow draws many visitors — some willing, some tripping dazed and blind along unseen ley lines.

"Oh Devouring Mother," the witch cries out, "let us be alone together!" But she knows that her entreaty is made in vain, having become grudgingly accustomed to her patron's primordial indifference. The Queen of Clay is always otherwise occupied. And Aster — the witch — realizes, though it rankles her: rites by a single supplicant with no extraordinary power are insufficient to sustain the Mother, our lady of such cavernous appetite.

Once, long ago, even longer than when the labyrinth was laid into the ground, this place saw a city which boasted a gorgeous central temple on the very spot that is now soft meadow and mild maze.

The temple's exterior was covered in intricate carvings, dark wood depicting legends of the city's history. The inner sanctum was cladded with blinding bright brass and inlaid patterns of electrum, that iridescent alloy of silver and gold.

This resplendent structure was dedicated to chthonic fertility goddess Elkatron, whose hunger is matched only by the grief that drives her to continually weep, weep, weep. Even today her tremendous, monstrous body is secreted far beneath the surface soil, down where rock meets smoke. Elkatron soaks the deep ground with her deluge of delirious tears.

Whatever finds its way to Elkatron is consumed. She feasts on the serpents of kings and the kings of serpents.

In the beginning the labyrinth was not the center of Wanderverse. Believe it or not, in those days Wanderverse had no center at all. But the man who would give it one had already been born.

He was not impressed with the world so far. It didn't meet his expectations. But that was fine since he'd never expected much of anything, making the expectations unmeetable. Nonetheless, this man was ambivalent about what he got.

He traipsed the land from town to village to hamlet to any other peculiar, particular small settlement. His own motives were pecuniary, after a fashion — the man was forever pursuing his fortune, which had slipped away up the road. Wistfully he recalled the days when it dogged him like a shadow.

This fellow's profession was traveling tinker, a jack of several trades who patched pots and pans, sharpened knives and axes, even did the simplest farrier jobs. He sold trinkets, brick-a-brack. Fancy candy made in molds, colorful like glass beads. And, tied up with string in crumpled kerchief bundles, a few arcane charms. But only if you struck him right when you asked.

The tinker bartered. He dickered. In between all of that he listened — listened with an open softness, absorbing snatches of gossip, family woes, the grim mesmer of renowned local campfire haunts, rumored portents, and singular dreams, be they sweet or unsettling. The tinker himself would pass along those tales he deemed fit to tell, especially any he'd heard twice over.

A certain story came first from a sturdy, surly farm wife. Later he heard it repeated by a jolly rendition of the same. It was like a lure, a temptation that snagged in his mind. The drama flashed bright in the corner of his eye as he rode long hours in the lurching cart, gazing ahead along the rough-hewn path that had been laboriously eked from brambled wilderness.

Lulled by his steady mule's gait and the motion of the vehicle, the tinker glimpsed the emerald shimmer of a peacock's tail and pondered what he'd heard about the Wailing Mother, the queen from ancient days who'd been worshiped by his ancestors.

Elkatron laments her five lost sons, and psychosanth blooms sprout five petals. One for each of her boys. She is fated to wail thus indefinitely. But many decades before her heart was first cruelly riven, she lived in eternity. It was her choice to leave.

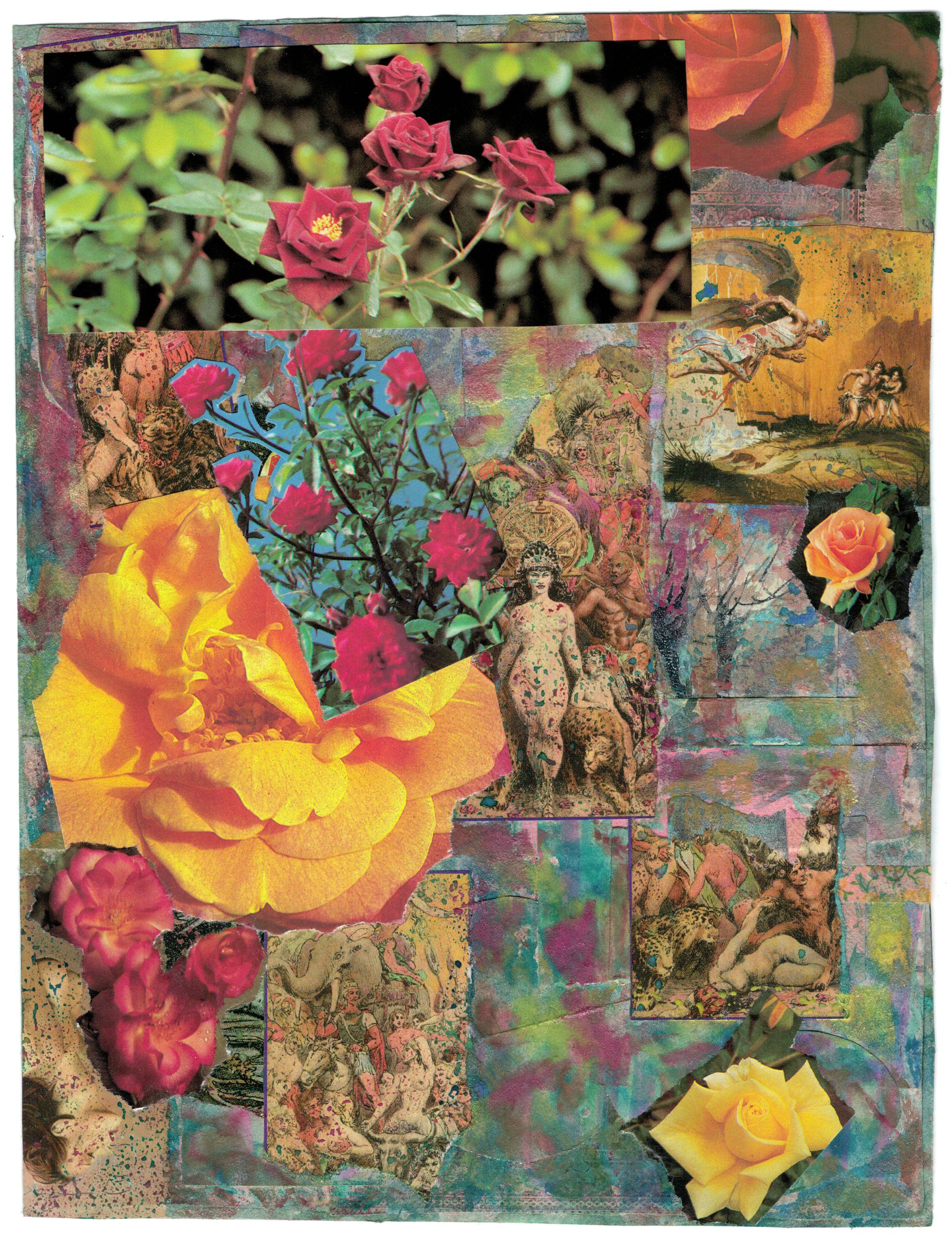

Elka was a sylphic naiad who dwelt among innumerable family members, a cornucopia of siblings and cousins, frolicking in the arboreal lushness of fairyland. Despite abundant playmates and the ambrosial surroundings, she was discontented. Itchy of spirit.

A single ever-stretching aeon for youthful frivolity was enough, Elka thought — perhaps it was too much. She was not like the other immortals; she found herself displeased with paradise. Elka was bored.

Creaky holy crones and the wizenedest of wizards would regale the fresher immortals with stories about adventuring with men, back in ye olden days. Just like Elm gasped and gaped at the reputed antics of goblins, Elka thrilled to hear the passion and risk revealed in these tales.

She developed a sharp longing to forget her diaphanous divinity, to escape this ethereal, nectarine realm and live as a human. Elka cherished her yearning and it bloomed like a water lily.

She knew, as they all did, that the king of fairyland governed the passage between worlds. It was his royal privilege to decide who ought cross either way — very few — or stay confined where they were. Most fell into the latter category (though only a handful ever considered the matter enough to realize it).

Elka approached the king's throne, a great black boulder jutting out through a tempestuous waterfall that terminated in the utter turmoil of white water crashing down and up all at once. As a naiad, Elka scarcely noticed the treacherous slipperiness of the wet rocks along which she flowed — her form was suited to these contours, and the way eased itself for her.

Elka asked, could she visit the humans, please?

The sovereign inclined his great whirling head as though in trepidation. Gently he breathed a warning against this idea. No, no, child. No.

Elka was stubborn, however. She cajoled. She wheedled. She begged. Not merely once; Elka returned repeatedly to entreat this favor from the king of fairyland.

For a long time, his judgment held resolute, harsh as the promontory where he seated his reign.

For a long time.

TO BE CONTINUED...