→ what z2z Public Messages is ←

Monday, October 28, 2019

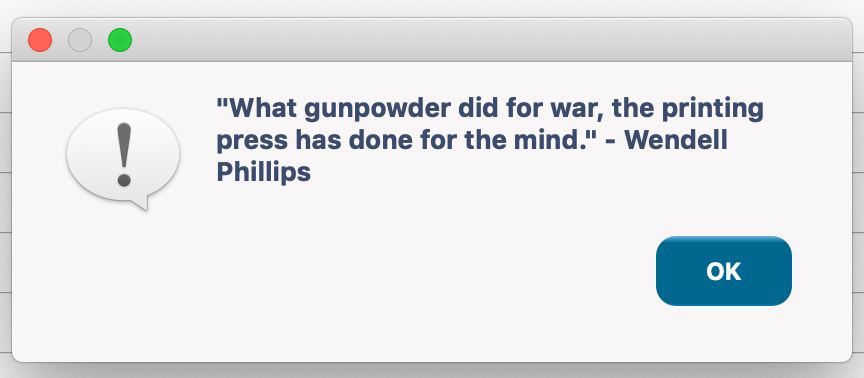

I looked up the quote. As a full sentence it's even more kick-ass:

What gunpowder did for war, the printing press has done for the mind, and the statesman is no longer clad in the steel of special education, but every reading man is his judge.

And! According to Wikipedia, that line is from an anti-slavery speech delivered in 1852, which you can read on Google Books. Wendell Phillips' antebellum analysis is just as rousing today — although perhaps ironic in its populism, given all that happened in the following decade. Anyway, I typed up a selection:

We are apt to feel ourselves overshadowed in the presence of colossal institutions. We are apt, in coming up to a meeting of this kind, to ask what a few hundred or a few thousand persons can do against the weight of government, the mountainous odds of majorities, the influence of the press, the power of the pulpit, the organization of parties, the omnipotence of wealth.

At times, to carry a favorite purpose, leading statesmen have endeavored to cajole the people into the idea that this age was like the past, and that "rub-a-dub agitation," as ours is contemptuously styled, was only to be despised. [...]

This "rub-a-dub agitation" [...] diminishes the confidence of the administration in its power to execute the Fugitive Slave Law, which it has imposed so insolently on the people. It acts on the reading men of the nation, and in that single fact is the whole story of change. Wherever you have a reading people, there every tongue, every press, is a power.

Mr. Webster, when he ridiculed in New York the agitation of the anti-slavery body, supposed he was living in old feudal times, when a statesman was an integral element in the State, an essential power in himself. He must have supposed himself speaking in those ages when a great man outweighed the masses. He finds now that he is living much later, in an age when the accumulated common sense of the people outweighs the greatest statesman or the most influential individual. [...]

Gunpowder came, and then any finger that could pull a trigger was equal to the highest born and the best disciplined; knightly armor and horses clad in steel went to ground before the courage and strength which dwelt in the arm of the peasant as well as that of the prince.

What gunpowder did for war, the printing press has done for the mind, and the statesman is no longer clad in the steel of special education, but every reading man is his judge. Every thoughtful man the country through, who makes up an opinion, is his jury to which he answers and the tribunal to which he must bow.

(I used [...] notation to indicate omissions and added line breaks for readability.)

In 1922, 70 years after Phillips' speech, Walter Lippmann published Public Opinion. The rest is history. Okay, the intervening period is also history.

My point: We can quibble with Phillips about plenty, and subsequent thinkers provide a necessary counterpoint. But he got it. He saw what matters, century upon century: Individual human liberty, and the tools that provide more of it. "The First Amendment is first for a reason," as Dave Chapelle said recently. "Second Amendment is just in case the first one doesn't work out." A-fucking-men.

Photo of two old books by Kiwihug.