Stahlblau, memetics analyst at The Outpost, kindly contributed the following guest post about divinity and the End Times — or the After Times, or whatever grimly liminal indexical you may prefer. He outlines a paradigm quite different from my own, for which I am grateful. I don't know about you, but my interest in eschatology has intensified exponentially of late. 2020 is that kinda year. Without any further ado...

Ancient gods were like mafia Dons: they embodied power. They were usually related to forces of nature, like thunder, water; and human activities such as war or agriculture. The gods were a basic fact of existence, a symbol of constant, perennial realities: that's why they were immortal. Religious people would try to harness the gods' power through different means, the same way we harness electricity or heat. Worship was instrumental: the whole point of ancient religion was to plug into the power sources the gods represented, which required certain rituals. Just like you would kiss Don Corleone's hand when asking for a favor, so you had to bow and sacrifice an ox in exchange of success.

Natural forces may inspire awe, but not adoration. Humans not only prayed to the gods, but also fought them, defied them, even copulated with them. Both gods and men were flawed, and shared a space within Creation. Some early Old Testament stories share a similar perspective, with Israelites trying to harness God's help against their enemies by way of fasting and other rituals. Basically, Israel's wars are used to illustrate who has the strongest, ablest god: who is on the side of the toughest guy on the block. Of course, every time they don't show proper reverence, the Israelites forfeit God's deliverance from Evil, and fall victim to their enemies.

Later biblical narratives, however, point to a different interpretation. In the Book of Job, a righteous man (Job) faces horrible calamities in what can only be described as an arbitrary, sadistic test of character: his children are all killed, and he becomes poor and sick. Job, in spite of this, remains a faithful believer. When he finally dares question God about the justice of his fate, however, he receives a long and enigmatic response (Job 40:1 to 42:6). In it, God describes His infinite power and the impenetrable nature of His designs, in a discourse that basically amounts to saying: you don't know anything about Me, so just shut up and know your place. Once he is shown God's power, Job falls to his knees, implores mercy, and thanks God for the graces given. Throughout his trials, he had held on to his integrity, but the effort was not enough to buy justification from God. In other words, there's nothing Job can do to bend or direct God's will. Him trying to probe God's motives is as absurd as a cockroach asking a person for answers.

Job's God can only be approached with a sense of terror, awe, and (maybe) faith. This is crucial: the goodness of God is not a hypothesis, a supposition of the believer; it's only a sense of hope based on God's word, with no other evidence other than the fact that the world has not ended yet. Whether God fulfills his promise or not remains to be seen: God's ultimate justice is always pending, out of time and space. This radical alterity, the supreme transcendence of a Creator God, is the true distinctive trait of Jewish monotheism.

In the New Testament, the archetype of God as Power was further shattered beyond recognition with Christ's abject death on behalf of sinners. To the ancient mind, this was both absurd and evil: who would die for a cockroach? The prospect seems immoral and stupid. Scandal to Jews, foolishness to gentiles (1 Corinthians 1:23). There was no way such a corrosive idea could enter the syncretistic Roman pantheon, which had accepted pretty much anything so far. Early Christianity had ruined the concept of God for everyone, which explains why the first martyrs were charged with atheism, and not with believing in the wrong God. Their beliefs were too dangerous: believing the End was near, they did not care for anything else.

Early Christians took very seriously their ethos of belonging to a Kingdom not being of this world. They hoped for the return of the Messiah, and His rule over a New Jerusalem where lion and lamb ate grass together and there was no more suffering. Naturally, they quickly developed a rich apocalyptic culture with its own literary corpus, the most significant part of which is of course the Book or Revelations. Parallel to this spiritual and religious process, however, a whole doctrine of political thought started to form, applying apocalyptic notions to the material world. After all, the writings left by the apostles made frequent references to contemporary people and events. They did so in a non explicit way, which allowed for said references to be adapted to different historical situations as time went on. The Beast, the Anti-Christ, etc, were all allusions to specific people, but later became archetypes which could be applied to newer occurrences.

One of these archetypes is the Katechon (from κατέχων, "the one who withholds"). The term is only found in 2 Thessalonians 2: 6-7. The text is a warning for Christians not to behave as if the Day of the Lord were on the brink of happening. Before the return of the Messiah, the Antichrist had to be revealed, leading to a period of lawlessness. The katechon was an entity which opposed the Antichrist's manifestation, withholding his revelation. It was the last wall to be breached before the events leading to the Second Coming were unleashed. Consequently, this made the removal of the katechon a precondition for the Day of the Lord and the fulfillment of final redemption.

The katechon kept the world permanently at the edge of the abyss represented by the Antichrist's rule; at the same time, it prevented the Second Coming. It was, thus, neither Christian nor Antichristian, an ambiguous figure one step away from the Apocalypse. In accelerationist jargon, it would correspond to the last decelerative force standing in the way of Collapse and the Singularity.

Tertullian initiated the tradition of identifying the katechon with the Roman Empire: an element which provided some semblance of order and law, preventing the chaos of the Antichrist. This notion allowed for a Rome-centered Christianity, and later provided justification for the role of a Catholic Universal Monarchy such as the one Charlemagne tried to embody. The might of the Holy Roman Empire was the only thing standing between Christendom and an imminent End of Time.

German political philosopher Carl Schmitt, although ambiguous towards Christianity, was a firm defender of the doctrine of the katechon. He saw it as the only possible explanation for Humanity having made it so far in History. Italian Marxist philosopher Paolo Virno (b. 1952) also uses the term katechon to refer to the elements in Human nature which stand in the way of the Bellum omnium contra omnes, the Hobbesian "war of all against all" that characterizes the state of nature. Interestingly, Katehon (no c) is the name of a Russian traditionalist think tank researching alternatives to current systems of global hegemony. One of its most prominent writers is Alexandr Dugin, an eurasianist thinker and former KGB employee who some claim was Putin's personal philosopher.

In any case, as a secular, bastardized formulation of Christianity, most Western liberal culture shares the Christian sensibility to apocalyptic reasoning. This is reflected in the political thought of both Left and Right, mainstream and fringe. Said apocalyptic sensibilities lie at the bottom of the excitement generated by every successive Happening™ promoted by the media, be it terrorism, climate change, coronavirus, or the prospect of racial war.

Specifically, the Progressive demands of radical political change immediately materializing appear to follow a Messianic imperative. Woke ideology and the latest BLM riots are shining examples of this, although for some beholders they may look more of the Antichrist than the Messiah's. Two questions remain: if this is true, who sits on the throne of the Katechon, and for how long?

Reminder: Stahlblau of The Outpost. His recent post "Liquefying the Heartland" is one of the most provocative works of futurism that I've read this year.

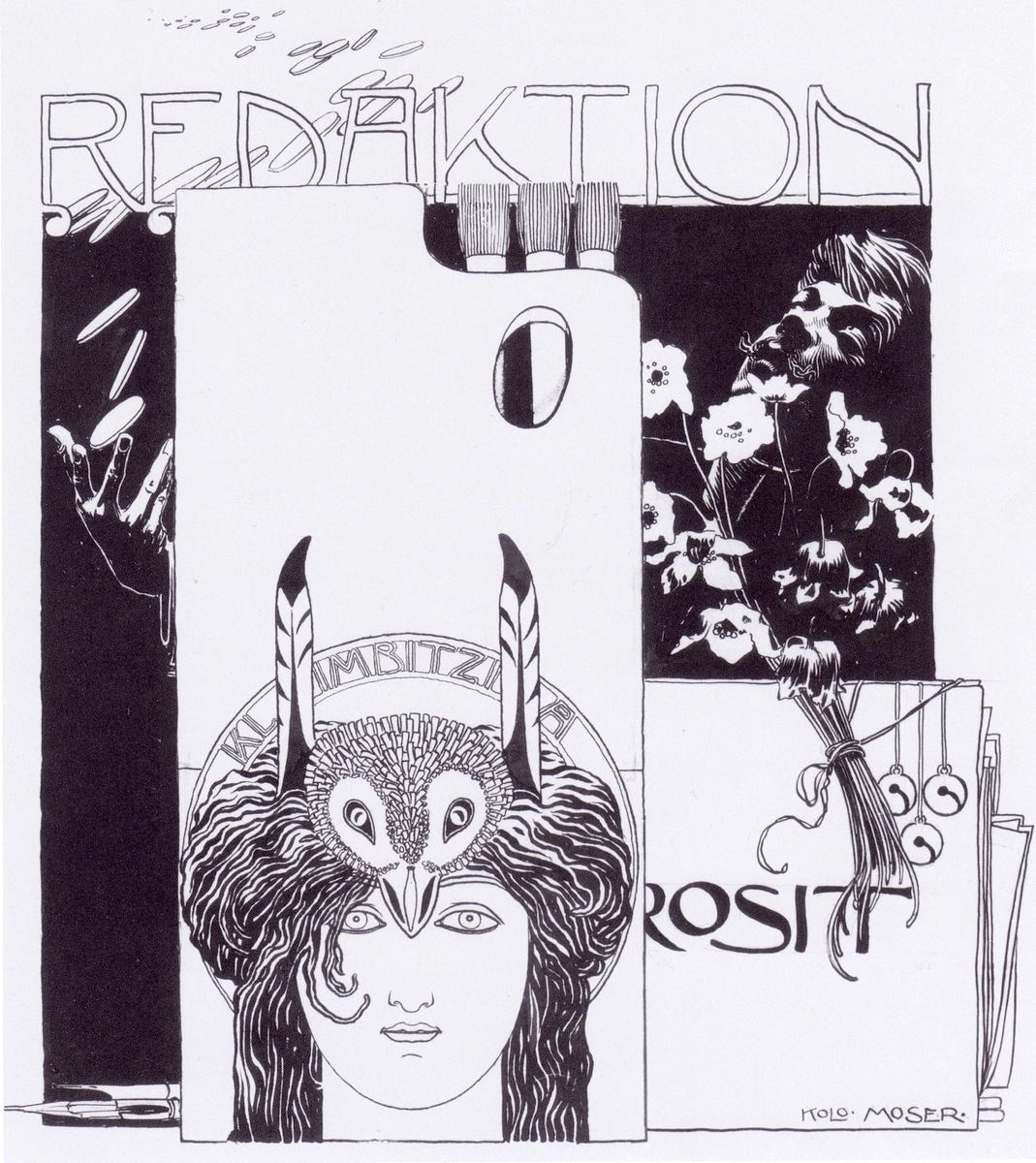

Header image via Joe Crawford:

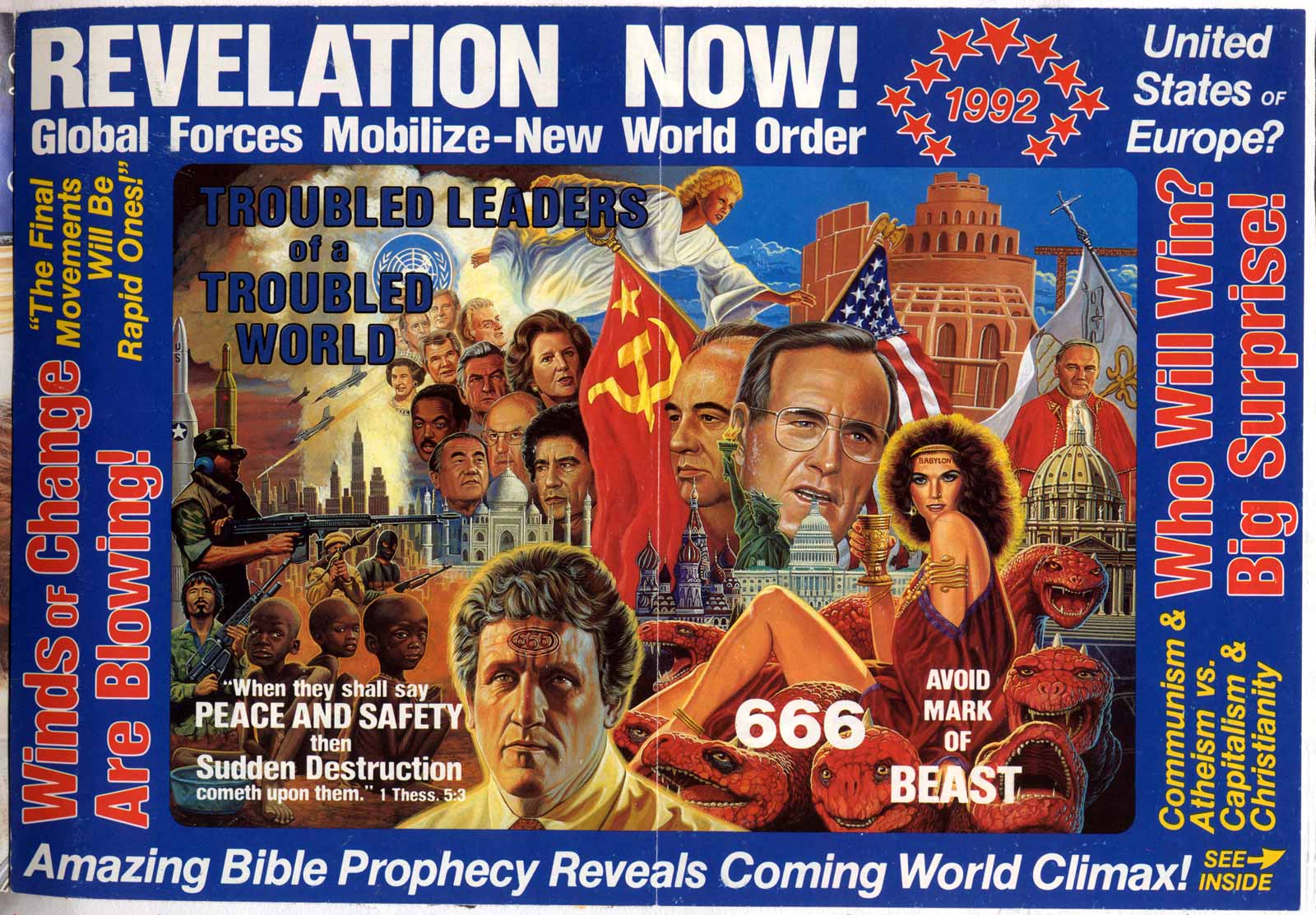

In 1992 I started a scrapbook I still have. This is a bizarre piece of junk mail I got. It was addressed to "Resident" at my apt in Charlottesville, Virginia.

It's filled with different people, and I suppose the beefy white guy with the 666 on his forehead is supposed to be Bill Clinton.

It's a peculiar artifact.

The sender was one "Seminars Unlimited" of PO Box 66, Keene Texas, 76059